Published: October 5, 2017

Thorough, thoughtful research reports like “Enhancing Equitable Access to Assistive Technologies in Canada” are the cornerstone of good decision-making. There is no question that as the number of older adults in Canada continues to grow, assistive technologies will play an increasingly important role in promoting active and healthy aging and independent living.

But from the perspective of this lifelong disabled person, reports, while necessary tools for change, can never capture the breadth of human drama and need associated with the difficulties and dilemmas the report addresses. Let me give you an example:

If you are suddenly in need, as I once was, of a ceiling lift, a custom–fitted wheelchair and more, the process for getting these assistive devices (or liberation technologies as my ilk call them) can be long and tortuous, filled frequently with snippy officials, soul–wracking, invasive forms to fill out, rushed medical specialists, cruel and lengthy wait times, and condescending attitudes.

And the cost of these devices can be surprisingly substantial, as I wrote about recently in The Walrus magazine and recently reprinted in the October issue of Readers Digest (this from an uncut version):

“Fortunately, my voice software version of Dragon Dictate only costs around $100. Over the years, however, I have spent tens of thousands of dollars on other liberation technologies: over $30,000 for installing an home elevator; more than $1,700 for my (third) ceiling lift; roughly $3,500 for my (fifth) manual wheelchair, a basic model, the Quickie 2; plus another $650 for what I’ve come to call “the most expensive cushion in the world” (my seventh or eighth)—layers of different types of foam, all of it designed to prevent pressure sores, which, if left untreated, could kill me. A power wheelchair can go as high as $20,000, which always amazes me since I bought my first car, a second-hand 1964 Pontiac Parisienne, for about $300.

“Purchasing an accessible van (around $12,000-$30,000+ for conversion, plus the original cost of the vehicle itself) is much more than I can afford, so I do the next best thing in a city where accessible public transit is fraught with problems: accessible taxis that cost me $45 one-way. Fortunately, my main driver of the past few years, the big-hearted Abdul, takes some of the sting out of the high price by regularly bringing me my favourite coffee — iced latte — when he picks me up in the morning.”

For several years in the 1990s I served on the board of what is now called Holland Bloorview children’s hospital and, boy, did we get reports, many of them concerning decisions about costs that ran into the millions. It could be overwhelming at times but I often found it really helpful to think about the following: What does this BIG decision actually mean to the child and family coming through the door? My experience is that hospital administrators, policymakers and others can often forget — not deliberately, or at least I hope not, but as a result of so much information and problem solving to be done –that real people have real problems and they need them addressed now, not at some point in the rosy future when, if the political/bureaucratic stars align, all sorts of services will be available on a timely, equitable basis.

Similarly, I recently served on an advisory committee of my local home care organization. There was a lot of talk of serving the client better, of making the operations more efficient and equitable. These are always good discussions to have, but too often they are just that: discussions. In that particular organization, they know the problems well but for reasons I cannot understand are not urgently addressing them. It’s the lack of urgency that always gets me. My wife one day put it this way, in her usual blunt fashion: “You know, sometimes I find that people in the helping professions are not terribly helpful.” Or, as the celebrated writer George Jonas once wrote: Wouldn’t it be nice in a healthcare situation to actually be treated like a valued customer?

I speak from the perspective of someone who has dealt with “the system” for decades. I know my way around it really well, and still I find it frustrating, demeaning and more difficult than it needs to be.

That said, reports like “Enhancing Equitable Access to Assistive Technologies in Canada” do matter. They bring much-needed attention and information to specific problems to government officials, policymakers and more.

As well, according to John Lavis, Canada Research Chair in Evidence-Informed Health Systems and Professor, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University: “This report is based on the best available evidence, not just personal opinion; it includes the systematically elicited input of people with lived experience; it’s not an end in itself, but an input to a dialogue that brings together key doers and thinkers to decide, ultimately, what can be done.” In other words, that means this report is several steps ahead of many others I’ve come across. It’s certainly a start.

Making your way through a system that is supposed to help you can be a lonely experience. At the same time, recovery and rehabilitation will always be a lonely experience to a certain extent. The individual also has responsibility to make it work, as I will describe – with some remarks on the difference a sneaker and ingenuity can make — on the evening of Thursday, October 5 at The Walrus Talks Mobility, presented by the McMaster Institute for Research on Aging.

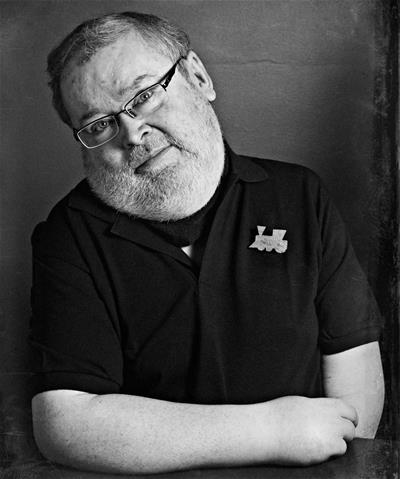

Stephen Trumper serves on the board of the Canadian Abilities Foundation. He is an independent writer and editor. He is also a journalism instructor at Ryerson University, and has worked as an editor at the Globe and Mail, Toronto Life and Financial Post Business.